Women’s History Month 2020

To mark Women’s History Month, we asked some of our female speakers attending this year’s History Festival to nominate their heroine and explain why they admire them.

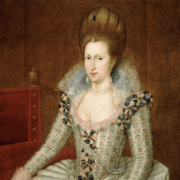

Tracy Borman: Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark is not one of our most famous queen consorts. Traditionally, she has been either overlooked by historians or dismissed as ‘anonymous’, ‘an uninteresting woman’ lacking in intellect and influence. She has even been described as a ‘dumb blonde’ who failed to captivate her more intelligent and cultured husband. More recent scholarship has proved such claims to be erroneous. Anne was culturally more sophisticated than James and was an active patron of music, art, and architecture in both Scotland and England. Neither can she be blamed for failing to hold her husband’s attention: James’s preference for his male favourites is well attested. In fact, as I discovered when researching my historical fiction trilogy (including the final instalment, The Fallen Angel, which I’ll be talking about at the Festival), there was a good deal more to Anne than met the eye. Far from sharing her husband’s staunchly Protestant faith, she was a closet Catholic whose networks stretched as far as the papacy in Rome. The Gunpowder Plotters, a group of Catholic gentlemen who planned to blow up King James and his entire parliament, always hinted at some ‘great patron’ who had supported their schemes but their identity was never revealed. I spun a plotline around the idea that it was Queen Anne herself. In a case of life imitating art, the more I researched her connection to the plotters, the more convinced I became that I might just be onto something.

Anne of Denmark is not one of our most famous queen consorts. Traditionally, she has been either overlooked by historians or dismissed as ‘anonymous’, ‘an uninteresting woman’ lacking in intellect and influence. She has even been described as a ‘dumb blonde’ who failed to captivate her more intelligent and cultured husband. More recent scholarship has proved such claims to be erroneous. Anne was culturally more sophisticated than James and was an active patron of music, art, and architecture in both Scotland and England. Neither can she be blamed for failing to hold her husband’s attention: James’s preference for his male favourites is well attested. In fact, as I discovered when researching my historical fiction trilogy (including the final instalment, The Fallen Angel, which I’ll be talking about at the Festival), there was a good deal more to Anne than met the eye. Far from sharing her husband’s staunchly Protestant faith, she was a closet Catholic whose networks stretched as far as the papacy in Rome. The Gunpowder Plotters, a group of Catholic gentlemen who planned to blow up King James and his entire parliament, always hinted at some ‘great patron’ who had supported their schemes but their identity was never revealed. I spun a plotline around the idea that it was Queen Anne herself. In a case of life imitating art, the more I researched her connection to the plotters, the more convinced I became that I might just be onto something.

Tracy will be telling Festival goers all about the real history behind her new novel, The Fallen Angel (Hodder & Stoughton, June 2020) in, ‘Angel Or Assassin? James I And The Duke Of Buckingham’.

Diana Preston: Cleopatra

Two millennia after her death, we still remember Cleopatra but for the wrong reasons. The image is of an exotic, erotic sex kitten, not the astute, intelligent, self-reliant, ambitious and sometimes ruthless queen who ruled Egypt alone for twenty years, keeping it independent of Rome. For that we must blame Roman propaganda. The Roman establishment feared her liaisons with and undoubted political influence over her two Roman lovers – first Julius Caesar and later Mark Antony. They suspected – with justice – that she planned to make her capital of Alexandria at least Rome’s equal. Her hopes finally foundered when, in 30 BCE, Antony died in her arms after his defeat by Octavian, the future Emperor Augustus. Even then the thirty-nine-year old queen kept control. Rather than be paraded by Octavian in chains through Rome, she took her own life. Immediately, the Roman propaganda machine went into overdrive depicting her as a nymphomaniac witch who had seduced a good Roman – Antony – from his duty. Clay oil lamps depicted her squatting obscenely on a phallus. The gifted, heroic woman who had dominated her country and influenced the Mediterranean world in a male age was expunged.

Two millennia after her death, we still remember Cleopatra but for the wrong reasons. The image is of an exotic, erotic sex kitten, not the astute, intelligent, self-reliant, ambitious and sometimes ruthless queen who ruled Egypt alone for twenty years, keeping it independent of Rome. For that we must blame Roman propaganda. The Roman establishment feared her liaisons with and undoubted political influence over her two Roman lovers – first Julius Caesar and later Mark Antony. They suspected – with justice – that she planned to make her capital of Alexandria at least Rome’s equal. Her hopes finally foundered when, in 30 BCE, Antony died in her arms after his defeat by Octavian, the future Emperor Augustus. Even then the thirty-nine-year old queen kept control. Rather than be paraded by Octavian in chains through Rome, she took her own life. Immediately, the Roman propaganda machine went into overdrive depicting her as a nymphomaniac witch who had seduced a good Roman – Antony – from his duty. Clay oil lamps depicted her squatting obscenely on a phallus. The gifted, heroic woman who had dominated her country and influenced the Mediterranean world in a male age was expunged.

Diana will be speaking at Chalke Valley History Festival 2020 about Eight Days At Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt & Stalin Shaped The Post-War World

Tracy Chevalier: Mary Anning

I nominate Mary Anning, the 19th-century fossil hunter from Lyme Regis. Mary was a working class woman – two strikes against her at the time – who discovered some of the first complete ichthyosaur and plesiosaur fossils on the Jurassic Coast.

She was self-taught, and held her own amongst the middle-class Oxbridge men she found fossils for. Without her discoveries the nascent field of palaeontology would have been taken much longer to progress.

Tracy’s CVHF talk is ‘Stitches In Time: Glimpses of Winchester History Through Its Cathedral Cushions.’

Annabel Venning: Queen Boudicca

Strong, brave, and self-sacrificing, Queen Boudicca, is the ultimate historical heroine.

When her husband Prasutagus, ruler of the Iceni died, the Romans annexed his kingdom, stole the lands of the tribal leaders and are said to have stripped and flogged Boudicca and raped her daughters. Boudicca swore vengeance but, cannily, she bided her time, waiting until the Romans were busy fighting in Wales

Then she led the Iceni in a revolt against them, burning their provincial capital, Camulodunum (Colchester) and Verulamium (St Albans to the ground, attacking military posts and killing 70,000 Romans.

She was eventually defeated but she and her daughters committed suicide rather than be captured.

Although she was ultimately unsuccessful, Boudicca’s ability to unite her tribe behind her and her courage in fighting for what was rightfully hers, pitting herself and her army against the might of the Roman Empire, is utterly admirable – and clear evidence that women were never the weaker sex.

In her CVHF talk, ‘To War With the Walkers’, Annabel will tell the enthralling and moving tales of her relatives, six ordinary young men and women, who each faced an extraordinary struggle for survival during World War II.

Dr Helen Fry: Marie Curie

My heroine is Marie Curie – she was an inspiration for her medical breakthroughs in radioactivity and physics that has transformed medicine for over a century.

As the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize, and first to receive it twice, she overturned ideas in chemistry and Physics, making groundbreaking discoveries, whilst transcending the gender challenges of her day. She sacrificed her life and died as a result of her research, but improved the lives of millions of others.

Helen will be at CVHF with a talk entitled, ‘The Walls Have Ears: The Greatest Intelligence Operation of World War II’.

Catherine Fletcher: Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia, daughter of Pope Alexander VI, is mainly famous thanks to the lurid claims of incest and murder levelled against her family.

But in fact she was a skilful politician and entrepreneur, who during her third marriage managed military affairs while her husband was away at war and almost doubled her annual income with some remarkable land reclamation and agricultural projects.

When it comes to historical heroines, popular reputation is rarely the whole story.

Catherine will be at Chalke Valley History Festival this June to talk about ‘Beauty And The Terror: An Alternative History of the Italian Renaissance’.

Tessa Keswick: Soong May-Ling

Married to the formidable Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-Shek in 1927 Soong May-Ling lived and worked at her husband’s side at the forefront of the dramatic political and social upheavals which convulsed China over the next decades. After Chiang formed the Nationalist Government in 1928 May-Ling became a committed First Lady of the nation. The Nationalist Government under Chiang faced down Chinese Warlords, the Communist insurgency, followed by the Japanese War until the Communist came to power in 1949. Mme Chiang and her husband retreated to Taiwan where he founded the Republic of China which formally exists to this day.

A member of the powerful Soong family, May-Ling was educated in America in a Southern Methodist school and at Wesleyan University. May-Ling’s international education was invaluable to her future development and informed her demanding career in China. Early in her marriage to the traditionalist General Chiang she established herself as a fiercely independent woman. In a recorded class of wills she successfully made him bend his will to hers but in response she vowed: “With my husband, I would work ceaselessly to make China strong”. General Chiang later wrote in his diary that half of his victory was due to his wife.

Tessa’s CVHF talk is ‘The Colour of the Sky After Rain’, an extraordinary memoir of one woman’s experiences in China.

Amanda Mitchison: Jane Austen

I am nominating Jane Austen as my heroine. She may not seem a particularly gallant individual. Outwardly she didn’t ‘do’ much with her life—women in her time and in her social position couldn’t; their role was to sit, wait and watch.

And she did just this – she watched. Like many writers she led a life of seemingly interminable tedium. But quietly, so quietly she revolutionised the novel – writers from Charles Dickens and Leo Tolstoy through to Jonathan Franzen and Hilary Mantel all owe her a debt. Today if I’m ill, or very tired, I pick up a Jane Austen to reread. Her writing is still so fresh and funny and insightful.

Amanda is speaking at our Schools Festival about ‘Brunel: The Life, Times and Disasters of The Greatest Engineer-Cum-Showman.

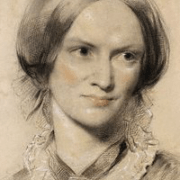

Laura Thompson: Charlotte Brontë

I have boundless admiration for Charlotte Brontë. She was such a fighter. What an inspiration she is to anybody who takes on the life of the writer! That life can still be quite nightmarish, so imagine what it was like for her, almost two centuries ago: this woman from Yorkshire whose passion and imagination seem barely contained by her tiny body, bashing away at publishers to get the Brontë oeuvre out into the world, fearlessly writing her way through grief at the deaths of her sisters.

She dealt with prejudice not just against her gender, but against the fact that she didn’t ‘conform’ to that gender, and she did so with a fierce dignity that was always true to her personality.

Laura is coming to Chalke Valley History Festival to talk about ‘The Lives of the Mitford Sisters’.

Katia Lysy: Iris Origo & Maria Montessori

My grandmother Iris Origo, through a true intellectual, felt the irresistible pull of engagement with the real world through social reform. She was fascinated by great figures who were able to put their ideals into practice, combining the life of the mind with pragmatic action. Maria Montessori – philosopher, physician and pedagogue – was such a one.

When Antonio and Iris Origo bought La Foce, a huge but impoverished estate set in a desolate valley in southern Tuscany, their aim was to bring prosperity and civilization to one of Italy’s most backward regions, the Val d’Orcia. A supremely ambitious project based on concrete action, in which land reclamation and agricultural innovation went hand in hand with social measures. Helping the farmers of the Val d’Orcia to create for themselves a happier, healthier life also meant providing an education for their children. And the Casa dei Bambini at La Foce, named after Maria Montessori’s famous schools, was inspired by the famous educator and her revolutionary ideas.

You can hear Katia talk about her grandmother, Dame Iris Origo at Chalke Valley History Festival this June.

Dr Janet Dickinson: Mildred Cecil

Mildred Cecil (neé Cooke), Lady Burghley was a remarkable woman who lived through a dynamic age. Born in 1526, she came from a family of female scholars and was considered an exceptional linguist, given to writing letters in fluent classical Greek. Over her life Mildred built a reputation for piety and charity, assembled an important private library, funded scholars at St John’s College in Cambridge and made careful provisions in her will, directing several of her bequests towards training those in need to acquire new skills for work. Of her five children just one survived her at the time of her death in 1589, though we know little of her emotional response to these losses. In common with many women of her age, our glimpses of Mildred are fleeting, but we know her to have been actively involved in politics and governance, corresponding with her husband William and others. She was the subject of a striking portrait, her face marked with the strain of a difficult pregnancy, asserting her place in historical memory as a woman of unusual strength. Without her, there can be no doubt that William would not have been able to achieve all that he did as chief advisor to Elizabeth I.

Janet is speaking at our Schools Festival about ‘Elizabeth I, William Cecil and The Question of Leadership.’

Daisy Dunn: Sappho

My historical heroine is Sappho, an immensely talented poet who was born on the island of Lesbos in the seventh century BC. In one of her finest poems, she described how her tongue was paralysed and her vision impaired as she jealously watched a woman she loved enjoying the attentions of somebody else. In another, she likened her beloved, Anaktoria, to the beautiful Helen of Troy.

Although Sappho is said to have married a man, the innovative poems in which she expressed her passion for women have ensured that she remains the ‘Lesbian’ poet of Lesbos in our imagination. It is rare to find a female voice preserved from antiquity. I admire hers for its candour and spirit.

Daisy CVHF talk is ‘In The Shadow Of Vesuvius: A Life of Pliny’.

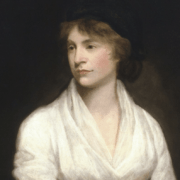

Caryn Mandabach: Mary Wollstonecraft

Why is Mary Wollstonecraft my historical inspiration? Because Wollstonecraft was a radical! She was an English writer, philosopher, and pioneer of the feminist movement in Britain. She is best remembered for her powerful polemical book, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – published in 1792 and still referenced today – in which she challenged the deeply entrenched misogyny of 18th century society by arguing that women deserved equal rights to men. Wollstonecraft lived the radical ideals she preached, refusing to marry her lovers until she became pregnant by William Godwin, and by keeping a separate apartment to Godwin after their marriage to maintain her independence.

Television Producer, Caryn Mandabach, will be at Chalke Valley History Festival to talk about her hit series, Peaky Blinders.

Agnès C. Poirier: Simone Veil

Few figures since Charles de Gaulle have enjoyed such respect and adoration in France. Simone Veil was of a rare breed who inspired admiration in generations of French people, regardless of their political leanings. Her dignity, strength and beauty made her a French symbol, now resting at the Paris Panthéon alongside Victor Hugo, Marie Curie, Zola, Voltaire and Rousseau.

Veil, a survivor of Auschwitz who lost both her parents and a brother in the hell of the camps, always spoke softly yet forcefully about the war’s darkest hours. However, she didn’t let it define her. She would study, work and be an independent woman, as her mother had urged her before dying of typhus in March 1945. Her experience in Auschwitz profoundly informed her love for the European project and its construction, with, at its heart, the reconciliation with Germany. The moment of her election as the first president of the European parliament in 1979 was intense with restrained emotion.

Parliamentarians rose from their seat, one after the other, turning towards her, applauding louder and louder. Film footage shows her smiling timidly, but her eyes say it all.

A few years earlier, Veil had led the mother of all legal battles at the French parliament, defending women’s right to abortion.

Veil had the peculiarity of being too revolutionary for the right and her political family and too bourgeoise for the left. She didn’t campaign for the legalisation of abortion out of ideology, but out of humanism. She couldn’t bear the idea that in the early 1970s, especially after the events of May 1968, French women were still forced to travel either to Switzerland or England to terminate unwanted pregnancies, or face both the distress and health risks of using an illegal abortionist.

On 26 November 1974, wearing a blue dress and a string of pearls, the 47-year-old Veil addressed the French national assembly. She was calm and determined: 200,000 French women were living the distress of clandestine abortion each year – it was time to end such suffering, she said.

The debates that followed lasted for 72 hours. Veil suffered despicable insults, especially from her political family. But supported by the president, Giscard d’Estaing, and the prime minister, Jacques Chirac, she won the vote at 3.40am on 29 November.

Agnès C. Poirier will be at Chalke Valley History Festival to talk about ‘Notre Dame: The Soul Of France’ (published 2 April 2020).

Alexandra Richie: Irene Sendler

I would like to nominate Irena Sendler, heroine of the Jewish children of Warsaw.

I would like to nominate Irena Sendler, heroine of the Jewish children of Warsaw.

Irene Sendler was a Polish Catholic social worker who was 29 when war broke out. She was horrified by the sheer brutality of the Nazi occupation, and used her position in the Warsaw Welfare Department to give aid to those in need. In November 1940 the Germans created the Warsaw Ghetto, sealing 400,000 people into what was in effect a gigantic prison. Sendler was determined to help and managed to get a permit which allowed her inside the Ghetto walls to assist the sick and dying as best she could. In September 1942 the Council For Aid to Jews, code named ‘Zegota’, was founded in Warsaw in order to help the Jews of Poland now facing the mass deportations to Treblinka; having heard of Sendler’s work Zegota appointed her as the head of their children’s department. With their support Sendler saved hundreds of children, smuggling them out of the Ghetto through sewers or via dug out basements. The children were given new identification cards and were hidden with families or in convents or anywhere else that could be found. Sendler preserved the true identities of all the children but tragically most of the parents were murdered in Treblinka and the families were never re-united.

Irena Sendler was named one of the Righteous Among the Nations in 1965. She died on 12 May 2008, a beacon of humanity to us all.

Alex will be at speaking about ‘The Battle For Berlin’ at Chalke Valley History Festival 2020.

Joanna Grochowicz

Jane Lady Franklin was well into middle age when her husband, the famed polar explorer Sir John Franklin, disappeared in the Canadian Arctic in the mid-1840s. At a time when a woman’s ability to influence was severely limited, she single-handedly persuaded the Admiralty, monarchs and heads of state, successive British governments, prominent individuals and a swathe of contemporary celebrities to support and fund her search for the missing men. Securing the greatest names in maritime and polar exploration to lead her many rescue expeditions, she also managed to capture the hearts of an entire nation through the pioneering use of the press, theatre and popular music. Over the course of three decades, Lady Franklin’s rescue efforts yielded little, however the 30 or so expeditions to the Canadian Arctic that she inspired, significantly broadened knowledge of the Arctic and resulted in extensive mapping of hitherto unknown regions.

Jane Lady Franklin was well into middle age when her husband, the famed polar explorer Sir John Franklin, disappeared in the Canadian Arctic in the mid-1840s. At a time when a woman’s ability to influence was severely limited, she single-handedly persuaded the Admiralty, monarchs and heads of state, successive British governments, prominent individuals and a swathe of contemporary celebrities to support and fund her search for the missing men. Securing the greatest names in maritime and polar exploration to lead her many rescue expeditions, she also managed to capture the hearts of an entire nation through the pioneering use of the press, theatre and popular music. Over the course of three decades, Lady Franklin’s rescue efforts yielded little, however the 30 or so expeditions to the Canadian Arctic that she inspired, significantly broadened knowledge of the Arctic and resulted in extensive mapping of hitherto unknown regions.

Joanna will be speaking about ‘Amundsen and the Race to the South Pole’ at CVHF and also at our Schools Festival.