Tag Archive for: Romans

THE SCOTTISH CAMPAIGNS OF SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS

/in History Hub, Writing/by Simon ElliottThis article was first published in Turning Points of the Ancient World on 18 March 2018.

The year was AD 207. In Rome the great warrior-Emperor, Septimius Severus, was bored. He’d hacked his way to power in AD 193 in the ‘Year of Five Emperors’, then fought two campaigns in the East (including the sack of the Parthian capital Ctesiphon). He had seen off the usurpation of the British governor Clodius Albinus and campaigned in his native North Africa. But now, he was reduced to fretting about his squabbling sons, Caracalla and Geta, in the Imperial capital.

Then, a golden opportunity presented itself for one final stab at glory, in far off Britannia, the ‘Wild West’ of the Roman Empire. This story is told in book form for the first time by archaeologist and historian Simon Elliott in his new work ‘Septimius Severus in Scotland: the Northern Campaigns of the First Hammer of the Scots’. Below, he gives a brief insight into his work as an introduction to this new appreciation of what was the largest campaigning army ever to be gathered and unleashed in the islands of Britain.

The Scottish Campaigns of Septimius Severus

Britannia was always a troubled province, particularly at the beginning of the 3rd century AD after Albinus’ attempt to seize the purple in AD 196/ 197. Having suffered periodic unrest along the northern border throughout the 2nd century AD, two major tribal confederations had emerged in the region of modern Scotland by AD 180.

These were the Maeatae (based in the central Midland Valley either side of the Clyde – Firth of Forth line) and the Caledonians to their north. At the end of the 2nd century, after Albinus’ failure, the then governor Virius Lupus had been forced to pay huge indemnities to both to prevent further trouble.

The Battle of Lugdunum: 197 AD. A significant proportion of Albinus’ army had been troops from the British legions. Artwork by © Johnny Shumate

These enormous injections of prestigious wealth to the northern elites of unconquered Briton further assisted the coalescence of power among their leaders, and trouble again erupted at the beginning of the 3rd century AD. This was quickly stamped out by Lupus and his successor Lucius Alfenus Senecio who then began to rebuild the northern defences which had fallen into disrepair after Albinus’ usurpation attempt. However, in AD 206/ 207 a disaster of some kind occurred in the North. This was dramatic enough for Senecio to write an urgent appeal to Severus in Rome. In it, he said that the province was in danger of being overrun and he requested either more troops or the Emperor himself to intervene in the province.

Severus’ response was ‘shock and awe’ writ large. He decided to launch an expeditio felicissima Brittannica. For this he gathered his wife Julia Domna, the bickering Caracalla and Geta, key Senators and courtiers, the Imperial fiscus treasury, his Praetorian Guard, the legio II Parthica – which he had based near Rome – and vexillations from all the crack legions and auxiliary units along the Rhine and Danubian frontiers. The whole were transported to Britain by the Classis Britannica in the spring of AD 208.

On his arrival, he established York as his Imperial capital. There he was joined by the provincial incumbent legions – legio VI Victrixalready based there, legio II Augusta from Caerleon and legio XX Valeria Victrix from Chester – together with the auxiliary units based in Britain. This gave him an enormous force totalling 50,000 men, together with the 7,000 sailors and marines of the regional fleet.

To support such a colossal force the fort, harbor and supply base at South Shields was selected as the main supply depot. The existing site was dramatically extended, with immense new granaries being built that could hold in total 2,500 tonnes of grain. This was enough to feed the whole army for two months. From South Shields the ships of the Classis Britannica fulfilled the fleet’s transport role, using the Tyne and eastern coastal routes to keep the army on the move once the campaign began. This included extensive use of the regional river systems wherever possible. Meanwhile the fort at Corbridge on Dere Street, just short of Hadrian’s Wall, was also upgraded, again for use as a major supply base. Here the granaries had been rebuilt, even before Severus’ arrival.

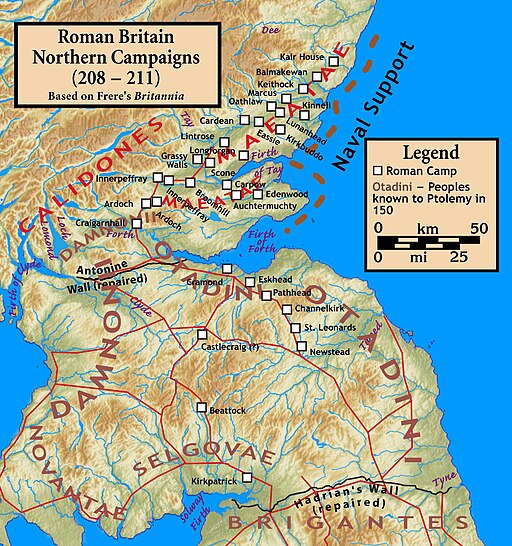

When all was ready in the spring of AD 209, Severus launched the first of his two assaults against the Maeatae and Caledonians in the far north of the province. Joined by Caracalla, he left Geta behind in York to take charge of the Imperial administration with the support of Julia Domna. The immense force marched north along Dere Street, crossing Hadrian’s Wall and then hammering through the Scottish Borders, destroying all before it. The whole region was cleansed of opposition, and, notably at this time, the Antonine fort at Vindolanda south of the Wall was demolished, with Late Iron-Age roundhouses being built there on a Roman grid pattern instead. This could have been a concentration camp for the displaced local population.

Today we can trace the line of march north through the Scottish Borders by following the sequence of enormous 67ha marching camps which were built to house and protect the army at the end of each day’s march. These are at Newstead, St Leonards (the largest at 70 ha), Channelkirk and Pathhead. Any resistance here would have been in the form of defended settlements such as hillforts, which were quickly stormed and destroyed.

Severus next reached the Firth of Forth at Inveresk where Dere Street turned west to cross the River Esk crossing. He then re-built the old Antonine fort, supply base and harbor at Cramond to serve as the next link in his supply chain after South Shields. Then he built a bridge of 900 boats at South Queensferry, before dividing the force into two separate but still huge legionary spearheads. The larger featured two thirds of his available troops (most likely with the three British legions who were used to campaigning in this theatre) under the fitter Caracalla. Meanwhile the smaller one featured the Praetorian Guard, other guard units and the legio II Parthica, under the ailing Severus, who was suffering from severe gout at the time. The other units in the overall force such as the auxilia were divided between the two as required.

Caracalla now led his larger force in a lightning strike south west to north east directly along the Highland Boundary Fault. As he progressed he built a sequence of 54 ha marching camps to seal off the Highlands from the Maeatae and Caledonians who were living in the central and northern Midland Valley. These camps were located at Househill Dunipace near Falkirk (the stopping off point before crossing the Forth), Ardoch at the south western end of the Gask Ridge, Innerpeffray East, Grassy Walls, Cardean, Battledykes, Balmakewan and Kair House. The latter location was only 13km south west of Stonehaven on the coast, where the Highland line visibly converged with the sea.

With the Highlands and the route northwards to the Moray and Buchan Lowlands now sealed off, the Emperor next sent the Classis Britannica along the coast which was also sealed off. This left the Maetae and Caledonians in the central and northern Midland Valley in a very perilous position as they had nowhere to run to.

Severus now took full advantage, leading his second legionary spearhead across the bridge of boats on the Firth of Forth again. However, instead of following Caracalla, he headed directly north across Fife to the River Tay, through land heavily settled by the Maeatae. He built two further marching camps to secure his line of march, 25ha in size, at Auchtermuchty and Edenwood. Reaching the Tay, he then rebuilt and re-manned the Flavian and Antonine fort, supply base and harbor at Carpow. This completed his east coast supply route to keep the enormous overall army in the field, now linking South Shields, Cramond and Carpow. Severus then built another bridge of boats, this time to cross the Tay, before striking directly north into the isolated northern Midland Valley, his legionaries brutalising all before them.

The campaign then became a grinding guerrilla war in the most horrific conditions, with weather even worse than usual. Both key primary sources, Cassius Dio and Herodian, graphically describe Severus’ campaign. Dio, in his Roman History, says (76.13):

“…as he (Severus) advanced through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down the forests, levelling the heights, filling up the swamps, and bridging the rivers; but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the soldiers for them to seize, in order that they might be lured on still further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men, in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died (clearly a massive exaggeration, but indicative of the difficulties the Romans faced). But Severus did not desist until he approached the extremity of the island.”

Meanwhile Herodian, in his History of the Roman Empire, says (3.14):

“…frequent battles and skirmishes occurred, and in these the Romans were victorious. But it was easy for the Britons to slip away; putting their knowledge of the surrounding area to good use, they disappeared in the woods and marshes. The Romans’ unfamiliarity with the terrain prolonged the war.”

Weight of numbers eventually told in the Roman’s favour and, with the entire regional economy desolated, the Maetae and Caledonians sued for peace. Unsurprisingly, the resulting treaty was very one sided in favour of Rome. Severus immediately proclaimed a famous victory, with he, Caracalla and Geta given the title Britannicus and with celebratory coins being struck to commemorate the event. Campaigning, at least in the short term, was now over to Imperial satisfaction. However, as always in the Roman experience of the far north of the Britain, such a state of comparative calm was not to last.

The Emperor, his sons and the military leadership wintered in York. Sadly for them however the terms which had so satisfied the Romans in AD 209 were not so agreeable to at least the Maeatae as in AD 210 they revolted again. The Caledonians predictably joined in, and Severus decided to go north again to settle matters once and for all. On this occasion he’d obviously had enough of the troublesome Britons, giving his famous order to kill all the natives his troops came across.

This second campaign re-enacted the AD 209 campaign exactly, though this time solely under Caracalla as Severus was too ill. It was even more brutal than the first as afterwards there was peace along the northern border for four generations afterwards, the longest in pre-modern times. Archaeological data is now emerging to show this was because of a major depopulation event, indicating something close to a genocide was committed by the Romans in the central and upper Midland Valley.

At the end of the campaigning season the remaining native leadership again sued for peace, though on even more onerous terms than previously. The ‘Severan surge’ then headed south again to winter once more near York, leaving large garrisons in place. However, any plans to remain in the far north were cut short when Severus died in York in February AD 211. Caracalla and Geta were far more interested in establishing their own power bases in Rome and quickly left. Severus’ huge force of 50,000 men then gradually returned to their own bases. The northern border was once more re-established on Hadrian’s Wall again, with all the effort of the AD 209 and 210 campaigns ultimately counting for naught excepting the unusually long-lasting peace afterwards.

Dr Simon Elliott is an archaeologist and historian specialising in Roman Britain and the Roman military. His PhD, at the University of Kent, focused on the presence of the latter in the south-east of Britain during the Roman occupation.

Dr Simon Elliott is an archaeologist and historian specialising in Roman Britain and the Roman military. His PhD, at the University of Kent, focused on the presence of the latter in the south-east of Britain during the Roman occupation.

Simon will be at CVHF on Friday 29th June to talk about Septimius Severus. Tickets are available here.

🎧 Schools Festival Audio: The Life of a Roman Legionary

/in Schools Festival Audio/by Ben KaneAudio from Chalke Valley History Festival for Schools 2017 with Ben Kane.

The Legacy of Rome: When Did the Roman Empire End?

/in History Hub, Talks & Audio/by Tom HollandRecording from Tom Holland’s talk, ‘The Legacy of Rome: When Did the Roman Empire End?’ for CVHF, Wednesday, 26th June 2013.

In AD 476, Romulus Augustulus, emperor in line to Augustus, Trajan and Constantine, was deposed by a German chieftain. It is an event that in most history books is identified as marking the end of the Roman Empire. But did it? Tom Holland explores whether the Romans themselves had any comprehension that their empire could possibly fall, traces the surprisingly obdurate survival of a Roman imperial identity across the centuries, and identifies the moment in history when the Roman Empire definitively came to an end. Told with his enormous knowledge and wide-ranging understanding of history, this was a hugely entertaining, provocative and utterly absorbing talk, proving why Tom Holland has become one of our foremost authorities and scholars of the Roman Empire.